The final chapter in a series on The Carpenters' A Song for You.

Part one here.

Part two here.

Part three here.

Part four here.

Part five here.

A Spotify songlist based on the track order for the cassette can be found here.

Just for the record - all sentiments expressed are speculation. Think of it as a pop-psychology fantasia on one of my favorite albums. Thanks for reading.

Sometimes, in the unhappiness of the day-to-day, we retreat into art for solace. What if the art doesn't help anymore? What if art, the thing that gives us joy, and freedom, becomes just another thing that keeps everyone out, another thing hanging over us, another possibility for failure? The Carpenters worked hard for their success, but as the man says, nothing comes for free.

The Carpenters entry into the genre of “The Road is Fuckin’ Tough” songs came with the penultimate track, “Road Ode.” The narrative of this album has come full circle, with the curtain raising of the opening song echoed here. But where before we were her sole listener, now she acknowledges that we are one of many - the audience is legion, intruding and keeping her simultaneously isolated, and never alone. She makes a point of telling us that her smile, her “Top of The World” charm, is a lie. That we, even we, her confidants, are one of the many whose expectations and demands are destroying her. The bright, hip, choruses belie the bitter, lonely lyrics. She’s onstage forever, so sad, so alone....

….and the crowd fades away. We are back at the beginning, reprising “A Song for You.” At first heavily reverbed, as if from a long distance she comes into focus, singing, once again, singing just to you . Don’t be fooled, this you is still the “you” of fantasy, the “you” that she has imagined as a way out of her loneliness. There lies the problem - it’s all one “you.” “You” are both the beloved, and the taskmaster. “You” are the only one who understands her, and the one who is driving her to destruction. You’re her parents, and the one person who can rescue her from the life she has created to try and please them. But really, you can’t save her, and she knows it. You oughta feel bad about that, too, because remember, she has predicted her own death (“And when my life is over/Remember when we were together”). You should feel guilt, but she would never be so gauche as to inflict it upon you. She is dying, not to make you feel bad, but because she loves you so much. Listen to how much she wants to please you (“I know your image of me is what I hope to be/I’ve treated you unkindly, but darling can’t you see?”). She will die trying to be that image of her you want to see.

This album shows the true story of Karen Carpenter in perfect Pop fashion: the crushing expectations, the impossible hopes of rescue and release, the longing for acceptance and the willingness to twist oneself into any shape to get it, the wistful looks back at an idyllic childhood that never was. We all know the next part of this story, the part where she dies in her parents’ home after a series of failed relationships and the slow suicide that is anorexia. But really, it was all here, available for us to see, both past and future. The future, her future, was here, in this album, all questions answered. She showed us the whole bitter script, asking for a different ending, and we were too seduced by her voice, her talent, by what she gave us, to hear her cry for help.

Thanks for reading. I hope you enjoyed it. If you want a copy of the whole thing in one document, let me know, and I'll make a pdf available.

Description

Before you speak, ask yourself, is it kind, is it necessary, is it true, does it improve on the silence? -Sathya Sai Baba

Tuesday, August 28, 2012

Monday, August 27, 2012

The Carpenters - Ready to Die, Part 5: Misplaced Childhood

An ongoing series on The Carpenters' A Song for You.

Part one here.

Part two here.

Part three here.

Part four here.

A Spotify songlist based on the track order for the cassette can be found here.

Just for the record - all sentiments expressed are speculation. Think of it as a pop-psychology fantasia on one of my favorite albums. Thanks for reading.

Karen grew up in the town of Downey, California, in the County of Los Angeles. Her folks moved there in the 60's with her and her brother. She lived with them until she was 26 years old, and she moved back in towards the end of her life. It's a common enough story, especially these days, with confused and battered 20-somethings moving back in with their folks, thrown back by an economy that has no place for them.

The differences are pretty crucial here, though. Karen was incredibly successful when she moved back in. She was a celebrity, a pop star, gifted with one of the most beautiful voices of her time, beloved by millions.

She was also anorexic, distraught over her divorce, and emotionally fragile. What was she looking for, moving back home shortly before she left therapy and died of heart failure? According to the myth of Karen's life, her parents were controlling and critical, and nothing she ever did was good enough, but it might be more complicated than that, and the album provides some interesting clues.

Again, we have the expert sequencing of this album coming into play with “Crystal Lullaby” up next. They know you’re a little raw, a little dicked in the head from the fighting and the confusion of the last song, and so they take you right back to childhood. This is regression at its finest, mommy and daddy coming in after the nightmare to soothe your brow. Richard (the nearest thing we have to an authority figure in this landscape of alternating pain and fantasy) sings the pre-chorus, his double-tracked vocals carrying you away, just like the lyric. This is probably the most sentimental and, superficially, the least interesting song on the album.

A case could be made, however, that here the Carpenters were singing about an idealized childhood experience that neither of them had ever lived. The ache in Karen’s voice is like the ache of country music when some hat act sings about small towns and simple values (when you know they grew up in, like, Dallas). It’s nostalgia for the never-lived - like hipsters paying tribute to 80’s and 90’s fashions they were too young to have worn the first time around. In this case, however, it’s nostalgia for a healthy childhood and a supportive family life, and someone to sing you to sleep.

In the next tune, “It’s Going to Take Some Time,” Karen sings, once again, of lost love, a theme already explored at length on this album. Everybody knows this is nowhere, albeit with her putting on a brave face for us. They’re on that Fender Rhodes piano sound, again, double tracked with an acoustic piano, in a perfectly pleasurable melancholy. Kicking flute solo in the instrumental break, too.

Now, “Bless the Beasts and the Children,” though it might seem on first glance to be pretty tame, has an earnest passion that belies its simple subject matter. Karen’s voice on the chorus is so sincere, so as-close-to-full-throttle-as-The-Carpenters-get, that she sells it. “Light their way/When the darkness surrounds them,” she sings - a plea, a prayer, a hymn. There are a couple of songs about childhood on this album, and every one seems to be calling back to an unreclaimable past, begging for a do-over.

Karen never really felt like anything she did was good enough, never felt like she was good enough. This is not an attitude with which we come into the world - it's learned. Something was missing in her life - a sense of love and acceptance, and as hard as she worked to make herself worthy of those things, she never really felt truly loved or understood.

The only real solace she seemed to find was in music, but as the final songs on the album indicate, even in music there was no escape.

Come back tomorrow for the final part. Thanks for reading!

Part one here.

Part two here.

Part three here.

Part four here.

A Spotify songlist based on the track order for the cassette can be found here.

Just for the record - all sentiments expressed are speculation. Think of it as a pop-psychology fantasia on one of my favorite albums. Thanks for reading.

Karen grew up in the town of Downey, California, in the County of Los Angeles. Her folks moved there in the 60's with her and her brother. She lived with them until she was 26 years old, and she moved back in towards the end of her life. It's a common enough story, especially these days, with confused and battered 20-somethings moving back in with their folks, thrown back by an economy that has no place for them.

The differences are pretty crucial here, though. Karen was incredibly successful when she moved back in. She was a celebrity, a pop star, gifted with one of the most beautiful voices of her time, beloved by millions.

She was also anorexic, distraught over her divorce, and emotionally fragile. What was she looking for, moving back home shortly before she left therapy and died of heart failure? According to the myth of Karen's life, her parents were controlling and critical, and nothing she ever did was good enough, but it might be more complicated than that, and the album provides some interesting clues.

Again, we have the expert sequencing of this album coming into play with “Crystal Lullaby” up next. They know you’re a little raw, a little dicked in the head from the fighting and the confusion of the last song, and so they take you right back to childhood. This is regression at its finest, mommy and daddy coming in after the nightmare to soothe your brow. Richard (the nearest thing we have to an authority figure in this landscape of alternating pain and fantasy) sings the pre-chorus, his double-tracked vocals carrying you away, just like the lyric. This is probably the most sentimental and, superficially, the least interesting song on the album.

A case could be made, however, that here the Carpenters were singing about an idealized childhood experience that neither of them had ever lived. The ache in Karen’s voice is like the ache of country music when some hat act sings about small towns and simple values (when you know they grew up in, like, Dallas). It’s nostalgia for the never-lived - like hipsters paying tribute to 80’s and 90’s fashions they were too young to have worn the first time around. In this case, however, it’s nostalgia for a healthy childhood and a supportive family life, and someone to sing you to sleep.

In the next tune, “It’s Going to Take Some Time,” Karen sings, once again, of lost love, a theme already explored at length on this album. Everybody knows this is nowhere, albeit with her putting on a brave face for us. They’re on that Fender Rhodes piano sound, again, double tracked with an acoustic piano, in a perfectly pleasurable melancholy. Kicking flute solo in the instrumental break, too.

Now, “Bless the Beasts and the Children,” though it might seem on first glance to be pretty tame, has an earnest passion that belies its simple subject matter. Karen’s voice on the chorus is so sincere, so as-close-to-full-throttle-as-The-Carpenters-get, that she sells it. “Light their way/When the darkness surrounds them,” she sings - a plea, a prayer, a hymn. There are a couple of songs about childhood on this album, and every one seems to be calling back to an unreclaimable past, begging for a do-over.

Karen never really felt like anything she did was good enough, never felt like she was good enough. This is not an attitude with which we come into the world - it's learned. Something was missing in her life - a sense of love and acceptance, and as hard as she worked to make herself worthy of those things, she never really felt truly loved or understood.

The only real solace she seemed to find was in music, but as the final songs on the album indicate, even in music there was no escape.

Come back tomorrow for the final part. Thanks for reading!

Thursday, August 23, 2012

The Carpenters - Ready to Die, Part 4: Love According to Karen

An ongoing series on The Carpenters' A Song for You.

Part one here.

Part two here.

Part three here.

A Spotify songlist based on the track order for the cassette can be found here.

Just for the record - all sentiments expressed are speculation. Think of it as a pop-psychology fantasia on one of my favorite albums. Thanks for reading.

Karen Carpenter dated. It's hard to imagine her dating, when you see videos of her from the mid to late-70's. She has a frailty that seems almost childlike, and all the sexiness of a wounded-bird. But apparently she dated some guys, including Tony Danza (!) and Mark Harmon. There isn't a lot of talk about those episodes. She married once, in 1980, and divorced two years later. All in all, with all the touring and working, there doesn't seem to have been a lot of room for romance in her life. Her deepest relationships seemed to have been with her family, and her music. So what did love look like to her? There are clues in the next songs.

After Richard has done his best to make nice in the previous couple of tunes, Karen eases us back into pathos with what at first plays like a declaration of love. On deeper listening, however, something less than healthy is revealed. In “I Won’t Last a Day Without You,” we’re back in Phil Collins territory, with the pretty pretty music covering up some seriously disturbed sentiment. A mellow, syrupy-stringed bridge does not help to lighten up the line “When there’s no getting over that rainbow/When my smallest of dreams won’t come true.” There’s a resignation in this song that she can’t quite smile her way through. She’s singing to her lover, almost in gratitude, but this song sounds like if dude ever leaves her, the next time he sees her will be in a casket.

And the gold medal in the self-pity olympics is... the next song: “Goodbye to Love.” Speaking of darkness, speaking of resignation, we’ve got, as our opening gambit, “I’ll say goodbye to love/No one ever cared if I should live or die....” There’s quite a bit of this, and just when we’re about to give up and take a bath with a toaster, the guitars come in, and suddenly we’re rocking as hard as the Carpenters ever rock in the history of ever. It’s only a taste, though, and then we’re right back into the smooth vocal stylings, singing despair into the beautiful void. After one more verse, the void itself seems to sing, heavenly “ah” vocals spinning sorrow into golden light. And over top of that comes, and you’ll just have to imagine this, but see, here descends Jesus, playing one of the most gorgeous guitar solos recorded by anyone. Seriously - go listen to it right now. It’s dirty, epically melodic, and somehow perfect for a song that makes a religion out of the phrase “Woe is me.”

“Hurting Each Other” is another example of this. Karen’s such a victim. As a child, listening on my parents stereo to this album, I found myself horrified and disturbed by this song. “Why would they hurt each other?” My only understanding of “hurt” was violence, and the thought of two people who obviously love each other (“No one in the world/ever had a love as sweet as my love/For nowhere in the world/Could there be a boy as true as you, love”) doing such violence seemed frightening. Ah, to always be so naive.This was the sound of a stomachache, red and black and grainy and angry and sad all at the same time. This was despair, smoothed until it shone, deep velvety darkness.

And there we have the three versions of the gospel according to Karen: 1. "I'm nothing without you;" 2. "Nobody loves me;" and 3. "I love you so much; why do you hurt me?" If anybody says any of these words to you, run, don't walk, and yet here we find one of the most beautiful voices of a generation singing all three within minutes of each other. I don't envision these as the sentiments of a mature heart and mind.

Where does such arrested emotional development have its roots? How does one end up simultaneously at the top of the charts, and yet so seemingly disconnected? Could living at home with your parents until you're 26 have something to do with it?

Next: Visions of a childhood that never was.

Part one here.

Part two here.

Part three here.

A Spotify songlist based on the track order for the cassette can be found here.

Just for the record - all sentiments expressed are speculation. Think of it as a pop-psychology fantasia on one of my favorite albums. Thanks for reading.

Karen Carpenter dated. It's hard to imagine her dating, when you see videos of her from the mid to late-70's. She has a frailty that seems almost childlike, and all the sexiness of a wounded-bird. But apparently she dated some guys, including Tony Danza (!) and Mark Harmon. There isn't a lot of talk about those episodes. She married once, in 1980, and divorced two years later. All in all, with all the touring and working, there doesn't seem to have been a lot of room for romance in her life. Her deepest relationships seemed to have been with her family, and her music. So what did love look like to her? There are clues in the next songs.

After Richard has done his best to make nice in the previous couple of tunes, Karen eases us back into pathos with what at first plays like a declaration of love. On deeper listening, however, something less than healthy is revealed. In “I Won’t Last a Day Without You,” we’re back in Phil Collins territory, with the pretty pretty music covering up some seriously disturbed sentiment. A mellow, syrupy-stringed bridge does not help to lighten up the line “When there’s no getting over that rainbow/When my smallest of dreams won’t come true.” There’s a resignation in this song that she can’t quite smile her way through. She’s singing to her lover, almost in gratitude, but this song sounds like if dude ever leaves her, the next time he sees her will be in a casket.

And the gold medal in the self-pity olympics is... the next song: “Goodbye to Love.” Speaking of darkness, speaking of resignation, we’ve got, as our opening gambit, “I’ll say goodbye to love/No one ever cared if I should live or die....” There’s quite a bit of this, and just when we’re about to give up and take a bath with a toaster, the guitars come in, and suddenly we’re rocking as hard as the Carpenters ever rock in the history of ever. It’s only a taste, though, and then we’re right back into the smooth vocal stylings, singing despair into the beautiful void. After one more verse, the void itself seems to sing, heavenly “ah” vocals spinning sorrow into golden light. And over top of that comes, and you’ll just have to imagine this, but see, here descends Jesus, playing one of the most gorgeous guitar solos recorded by anyone. Seriously - go listen to it right now. It’s dirty, epically melodic, and somehow perfect for a song that makes a religion out of the phrase “Woe is me.”

“Hurting Each Other” is another example of this. Karen’s such a victim. As a child, listening on my parents stereo to this album, I found myself horrified and disturbed by this song. “Why would they hurt each other?” My only understanding of “hurt” was violence, and the thought of two people who obviously love each other (“No one in the world/ever had a love as sweet as my love/For nowhere in the world/Could there be a boy as true as you, love”) doing such violence seemed frightening. Ah, to always be so naive.This was the sound of a stomachache, red and black and grainy and angry and sad all at the same time. This was despair, smoothed until it shone, deep velvety darkness.

And there we have the three versions of the gospel according to Karen: 1. "I'm nothing without you;" 2. "Nobody loves me;" and 3. "I love you so much; why do you hurt me?" If anybody says any of these words to you, run, don't walk, and yet here we find one of the most beautiful voices of a generation singing all three within minutes of each other. I don't envision these as the sentiments of a mature heart and mind.

Where does such arrested emotional development have its roots? How does one end up simultaneously at the top of the charts, and yet so seemingly disconnected? Could living at home with your parents until you're 26 have something to do with it?

Next: Visions of a childhood that never was.

Wednesday, August 22, 2012

The Carpenters - Ready to Die, Part 3: Lighten Up, Richard

An ongoing series on The Carpenters' A Song for You.

Part one here.

Part two here.

A Spotify songlist based on the track order for the cassette can be found here.

A Song for You takes a turn midway through side one. Richard, the peacemaker, to some people the Machiavellian mastermind who drove Karen to an early grave, comes around to lighten things up a little.

He begins with “Piano Picker,” a bit of fluff about how he got to be such a great pianist, and Exhibit A on this album in the case brought by many against The Carpenters on the charge of rampant and egregious corniness. The song bounces and tap dances like something straight out of the music halls circa nineteen-aught. One can imagine him playing this, mugging and grinning, to cheer Karen up when she was blue, keeping her in the studio, keeping her working.

An open letter, as an aside: Dear Richard. I heard you got really mad after director Todd Haynes suggested in the movie “Superstar” that you might be gay. Now, it’s not right to stereotype, but with your lisp coming through in stereo, even a child can tell you might not be like the other boys. Let me tell you, you are beautiful, no matter what they say, but if you don’t want people to think you’re gay, you might want to rethink lines like “Now the other guys are out playing with their girlfriends, and I’m still banging on the keys.” It’s fine! I’m a musician myself! I understand not fitting in, staying inside on beautiful days to practice, thinking about all the shit you sacrificed to do something that most people think of as “entertainment.” I even and especially get folks thinking you’re gay. Ultimately, you just have to do you. Be proud of who you are. All am saying is, really, you sound a little defensive. Sincerely, etc.

The nice Manhattan Transfer-like section in the middle, jazzy and tight and totally superfluous, really shows off Richard’s arranging skills. His talents as a musician, and as an artist, are on full display here, and the song doesn't overstay its welcome. It's the musical equivalent of the breezy fellow who just came into the party, shook some hands, told a few jokes, and then split, leaving a warm feeling and mild sense of vacancy.

Next comes the instrumental “Flat Baroque.” To keep the gay theme going, I used this song my freshman year in high school to soundtrack a mime performance I did of a hairdresser screwing up a customer’s ‘do. I minced about and pretended to cut hair, and mimed falling asleep and accidentally shaving my customer’s head. Yes, bad Scott, I stereotyped gays as flamboyant, effeminate hairdressers. It was 1984, and I’m sorry about that. The other kids loved it, and I think I got an A, but no excuses.This song is another jazzy little ditty with some nods to classical. There’s a basson line counterpoint that is charming as hell in this song, a highlight in a song whose sole purpose seems to be to charm and divert.

Richard served a crucial role in The Carpenters. He seemed to act as an anchor, keeping Karen grounded and working. It's easy to forget that he was his own person, an accomplished musician and arranger in his own right, and someone who was, I'm sure, deeply hurt by the early death of his sister. As light as he tried to make things, though, with his wit and his friendly demeanor, he couldn't really keep the truth of his sister's sorrow at bay.

Next: Back into the darkness, but gently, gently.

Part one here.

Part two here.

A Spotify songlist based on the track order for the cassette can be found here.

A Song for You takes a turn midway through side one. Richard, the peacemaker, to some people the Machiavellian mastermind who drove Karen to an early grave, comes around to lighten things up a little.

He begins with “Piano Picker,” a bit of fluff about how he got to be such a great pianist, and Exhibit A on this album in the case brought by many against The Carpenters on the charge of rampant and egregious corniness. The song bounces and tap dances like something straight out of the music halls circa nineteen-aught. One can imagine him playing this, mugging and grinning, to cheer Karen up when she was blue, keeping her in the studio, keeping her working.

An open letter, as an aside: Dear Richard. I heard you got really mad after director Todd Haynes suggested in the movie “Superstar” that you might be gay. Now, it’s not right to stereotype, but with your lisp coming through in stereo, even a child can tell you might not be like the other boys. Let me tell you, you are beautiful, no matter what they say, but if you don’t want people to think you’re gay, you might want to rethink lines like “Now the other guys are out playing with their girlfriends, and I’m still banging on the keys.” It’s fine! I’m a musician myself! I understand not fitting in, staying inside on beautiful days to practice, thinking about all the shit you sacrificed to do something that most people think of as “entertainment.” I even and especially get folks thinking you’re gay. Ultimately, you just have to do you. Be proud of who you are. All am saying is, really, you sound a little defensive. Sincerely, etc.

The nice Manhattan Transfer-like section in the middle, jazzy and tight and totally superfluous, really shows off Richard’s arranging skills. His talents as a musician, and as an artist, are on full display here, and the song doesn't overstay its welcome. It's the musical equivalent of the breezy fellow who just came into the party, shook some hands, told a few jokes, and then split, leaving a warm feeling and mild sense of vacancy.

Next comes the instrumental “Flat Baroque.” To keep the gay theme going, I used this song my freshman year in high school to soundtrack a mime performance I did of a hairdresser screwing up a customer’s ‘do. I minced about and pretended to cut hair, and mimed falling asleep and accidentally shaving my customer’s head. Yes, bad Scott, I stereotyped gays as flamboyant, effeminate hairdressers. It was 1984, and I’m sorry about that. The other kids loved it, and I think I got an A, but no excuses.This song is another jazzy little ditty with some nods to classical. There’s a basson line counterpoint that is charming as hell in this song, a highlight in a song whose sole purpose seems to be to charm and divert.

Richard served a crucial role in The Carpenters. He seemed to act as an anchor, keeping Karen grounded and working. It's easy to forget that he was his own person, an accomplished musician and arranger in his own right, and someone who was, I'm sure, deeply hurt by the early death of his sister. As light as he tried to make things, though, with his wit and his friendly demeanor, he couldn't really keep the truth of his sister's sorrow at bay.

Next: Back into the darkness, but gently, gently.

Playlist for Carpenters' A Song for You

Here's the playlist for The Carpenters' A Song for You in the order that I'll be talking about the tracks. This is the order that the tracks appeared on the cassette, as opposed to the album (now CD) track order.

Please feel free to listen and share! Thanks.

Tuesday, August 21, 2012

The Carpenters - Ready to Die, part 2: Two Sides to the Same Story

Here's part two of my five-part essay on The Carpenters' A Song for You. Please note that the track listing I follow here is based on the cassette (if you don't remember cassettes, please leave the blog, you're too young to be here), and NOT the album. I've created a Spotify playlist you can follow here which has the songs in the order I grew up on. If you want to start from the beginning, you can read part one here.

In the age of digital, music functions differently. The age of album-long artistic statements (outside of hip-hop, which still has enough grandiosity left to believe that you will listen straight through forty-five minutes of music padded out to seventy-four minutes by mostly-not-funny sketches that serve as interstitial scene changes) is mostly behind us. We listen to our music in discrete bites, savoring this flavor or that.

But once, not so long ago, every album was it's own entity. We pressed play, strapped on the headphones, and settled into the world of the artist. The track order was set with care, with a fine eye toward a cumulative impact. In A Song for You, a seeming dichotomy between two very different styles of song tell a more compelling story than either would have alone.

“A Song for You” acts as overture. A burnt orange curtain (the color of the cover) rises on a black stage, and a single spot clicks on. She is on stage, alone, singing specifically to you, and you are the only person in the universe. She may have “acted out her love in stages” but she’s not acting now. This is the final plea of someone who is desperate to connect. She sings “When my life is over/Remember when we were together”. These are not romantic nothings; she’s at the end.

Yes, it’s a downer, but it is, above all, sincere. There’s a moment in the bridge, when she demands you “listen to the melody/‘cause my love is in there hiding,” where her passion (chaste though it may be, hot with chastity, panting with abstinence), banked until now, blossoms into flame. Cosmic “ooh’s” rise in light and fall back into darkness. A saxophone, not the cliche of the smoky sax solo, but the mold from which the cliche is created, blows through a chorus and dissipates. Then, the voices sing once again, an upwelling of emotion, feeling rising to plateau, back to the bridge, almost apologizing for how much she feels, climbing back up to climax - the angels ascend and dissolve in ecstasy into the firmament. One more repeat of the chorus, and the song fades to the black of the silence between tracks.

In "Top of the World," the sun comes up. Rainbow dirigibles float dreamily over a technicolor landscape. This is a sort of suburban psychedelia, a perma-grin that seems to permeate the world. Everything is colored so vividly as to have been dipped in day-glo. The steel guitar and Rhodes piano combination is inspired: two of the happiest sounds ever created dueting to make sure you know that things are really, really nice. The quick dip into and back out of a capella at the end is lovely, as well. This is a beautiful little slip of a song, and, in sequencing, a good call after the aching sadness of the opener. The mellowness of Karen’s voice takes the bite out of this trip - all of the edges have been sanded off, and John Denver himself would have been pleased as punch to settle down in a world this suffused with golden light.

In these two songs, the dichotomy of the album is set: heartfelt, painful confession set in opposition to an idealized, beautiful world view. Two stories, looking in different directions, trying to ignore each other. There's just one problem.

One of these stories is actually true.

Thanks for sticking with it. Come back tomorrow for part three!

In the age of digital, music functions differently. The age of album-long artistic statements (outside of hip-hop, which still has enough grandiosity left to believe that you will listen straight through forty-five minutes of music padded out to seventy-four minutes by mostly-not-funny sketches that serve as interstitial scene changes) is mostly behind us. We listen to our music in discrete bites, savoring this flavor or that.

But once, not so long ago, every album was it's own entity. We pressed play, strapped on the headphones, and settled into the world of the artist. The track order was set with care, with a fine eye toward a cumulative impact. In A Song for You, a seeming dichotomy between two very different styles of song tell a more compelling story than either would have alone.

“A Song for You” acts as overture. A burnt orange curtain (the color of the cover) rises on a black stage, and a single spot clicks on. She is on stage, alone, singing specifically to you, and you are the only person in the universe. She may have “acted out her love in stages” but she’s not acting now. This is the final plea of someone who is desperate to connect. She sings “When my life is over/Remember when we were together”. These are not romantic nothings; she’s at the end.

Yes, it’s a downer, but it is, above all, sincere. There’s a moment in the bridge, when she demands you “listen to the melody/‘cause my love is in there hiding,” where her passion (chaste though it may be, hot with chastity, panting with abstinence), banked until now, blossoms into flame. Cosmic “ooh’s” rise in light and fall back into darkness. A saxophone, not the cliche of the smoky sax solo, but the mold from which the cliche is created, blows through a chorus and dissipates. Then, the voices sing once again, an upwelling of emotion, feeling rising to plateau, back to the bridge, almost apologizing for how much she feels, climbing back up to climax - the angels ascend and dissolve in ecstasy into the firmament. One more repeat of the chorus, and the song fades to the black of the silence between tracks.

In "Top of the World," the sun comes up. Rainbow dirigibles float dreamily over a technicolor landscape. This is a sort of suburban psychedelia, a perma-grin that seems to permeate the world. Everything is colored so vividly as to have been dipped in day-glo. The steel guitar and Rhodes piano combination is inspired: two of the happiest sounds ever created dueting to make sure you know that things are really, really nice. The quick dip into and back out of a capella at the end is lovely, as well. This is a beautiful little slip of a song, and, in sequencing, a good call after the aching sadness of the opener. The mellowness of Karen’s voice takes the bite out of this trip - all of the edges have been sanded off, and John Denver himself would have been pleased as punch to settle down in a world this suffused with golden light.

In these two songs, the dichotomy of the album is set: heartfelt, painful confession set in opposition to an idealized, beautiful world view. Two stories, looking in different directions, trying to ignore each other. There's just one problem.

One of these stories is actually true.

Thanks for sticking with it. Come back tomorrow for part three!

Monday, August 20, 2012

The Carpenters - Ready to Die: "A Song For You" as Suicide Note (part 1)

This is part 1 of a 5 part essay on The Carpenters' album A Song For You. I hope you like it!

(UPDATE: Looks like it'll be a bit more than 5! Check out subsequent days for further parts.)

Pop is the jester of modern music. While Rap is the new murder ballad and Dance is white noise for smoothing brain creases to blissful, oblivious ecstasy (Indie shuffles a few steps, shrugs, scribbles in its notebook, dreams of rocking hard), Pop can sneak in emotional truth under the radar. It makes no claims, no demands, promising only a smattering of pleasure for your three minutes investment. At the same time, it’s this very lack of pretense that allows Pop to do what many of the other genres are too cool to do - tell tales of obsession, madness, sorrow.

Karen Carpenter, along with her brother Richard as The Carpenters, made quintessential pop music of beauty and pain, smuggling in the angst under cover of precious arrangements, earworm hooks, and Karen’s silken voice. They made a career out of lovely, inconsequential, middle-of-the-road radio fodder, but they did one work of genius, an album that encapsulates a strange melding of pathos and prettiness: A Song for You.

This album, one of my parent’s favorite albums, the soundtrack to a hundred road trips in my youth, became almost an icon of pop music for me. The cover was simple - a silvery white heart, almost resembling a locket from a necklace, on a burnt orange field beneath the black Carpenters logo. Inside lay smooth, friendly, and, most of all, accessible music. But beneath the charming surfaces ran a river of reckless heartache, a pleasurable, almost luxuriant, wallowing in pain. It was seductive, and unsettling, and most of all, sad. Oceans of sad, a bummer the size of the world.

The delivery system for all this sorrow? That voice. Karen Carpenter’s contralto soothed and caressed. Yes, she sang of suffering, but it was a shared pain, and her voice ran its fingers through your hair and told you everything would be over soon. It was the seduction of no hope.

She sang from the bottom of a broken heart.

Oh, there were the funny songs, too, the songs that Richard sang, the clever little “Intermission" (“We’ll be right back/After we go/To the bathroom” all sung in a faux baroque that they must have thought was hilarious), but these were just interludes, a little wink to keep things light.

Pleasantries aside, this album, almost despite itself, told a story, and the story it inadvertently told was the story of a singer who knew she was going to die.

Come back tomorrow for part 2!

(UPDATE: Looks like it'll be a bit more than 5! Check out subsequent days for further parts.)

Pop is the jester of modern music. While Rap is the new murder ballad and Dance is white noise for smoothing brain creases to blissful, oblivious ecstasy (Indie shuffles a few steps, shrugs, scribbles in its notebook, dreams of rocking hard), Pop can sneak in emotional truth under the radar. It makes no claims, no demands, promising only a smattering of pleasure for your three minutes investment. At the same time, it’s this very lack of pretense that allows Pop to do what many of the other genres are too cool to do - tell tales of obsession, madness, sorrow.

Karen Carpenter, along with her brother Richard as The Carpenters, made quintessential pop music of beauty and pain, smuggling in the angst under cover of precious arrangements, earworm hooks, and Karen’s silken voice. They made a career out of lovely, inconsequential, middle-of-the-road radio fodder, but they did one work of genius, an album that encapsulates a strange melding of pathos and prettiness: A Song for You.

This album, one of my parent’s favorite albums, the soundtrack to a hundred road trips in my youth, became almost an icon of pop music for me. The cover was simple - a silvery white heart, almost resembling a locket from a necklace, on a burnt orange field beneath the black Carpenters logo. Inside lay smooth, friendly, and, most of all, accessible music. But beneath the charming surfaces ran a river of reckless heartache, a pleasurable, almost luxuriant, wallowing in pain. It was seductive, and unsettling, and most of all, sad. Oceans of sad, a bummer the size of the world.

The delivery system for all this sorrow? That voice. Karen Carpenter’s contralto soothed and caressed. Yes, she sang of suffering, but it was a shared pain, and her voice ran its fingers through your hair and told you everything would be over soon. It was the seduction of no hope.

She sang from the bottom of a broken heart.

Oh, there were the funny songs, too, the songs that Richard sang, the clever little “Intermission" (“We’ll be right back/After we go/To the bathroom” all sung in a faux baroque that they must have thought was hilarious), but these were just interludes, a little wink to keep things light.

Pleasantries aside, this album, almost despite itself, told a story, and the story it inadvertently told was the story of a singer who knew she was going to die.

Come back tomorrow for part 2!

Monday, August 13, 2012

What I talk about when I talk about swimming

It starts the moment I step on deck: anticipation in the smell of chlorine, antiseptic and biting, the echoing of splash and slap of bare feet. My breathing slows, despite the slight sick pit of my stomach. I know it will hurt. Maybe I’ll just skip it today. But by the time I’m in the water, it’s too late. The rhythm of the workout is already marching lockstep across jagged brainwaves, smoothing out ragged peaks into slow, smooth curves. Stroke, stroke, breathe, easy and loose.

All my thoughts disappear. Long ruminations, sentences, paragraphs, truncate into mantras, repetitive phrases, snippets of songs. The ache of my shoulders, the burn in my legs, they sing to me, too, my whole body become a verb, a motion in the water. The black line in tile along the bottom of the pool is a road above which I fly, hardly conscious except of the water, and my cutting through it.

The water is silk, medium and vehicle, that which I move through and that which I use to move. I don’t feel like working out today? Bullshit. Workouts are like Christmas, or being stoned. They are their own time, each time continuous with the previous instance, so that they form a single timestream, independent of my daily life, waiting for me to come back. Suspended until next time I step out on the deck, the next shock of the cold water as I dive in and begin to swim, disappearing into that long blue space between words and silence.

I finish the workout, and climb out clean, nothing but white noise between my ears.

All my thoughts disappear. Long ruminations, sentences, paragraphs, truncate into mantras, repetitive phrases, snippets of songs. The ache of my shoulders, the burn in my legs, they sing to me, too, my whole body become a verb, a motion in the water. The black line in tile along the bottom of the pool is a road above which I fly, hardly conscious except of the water, and my cutting through it.

The water is silk, medium and vehicle, that which I move through and that which I use to move. I don’t feel like working out today? Bullshit. Workouts are like Christmas, or being stoned. They are their own time, each time continuous with the previous instance, so that they form a single timestream, independent of my daily life, waiting for me to come back. Suspended until next time I step out on the deck, the next shock of the cold water as I dive in and begin to swim, disappearing into that long blue space between words and silence.

I finish the workout, and climb out clean, nothing but white noise between my ears.

Friday, August 3, 2012

Blind Spot

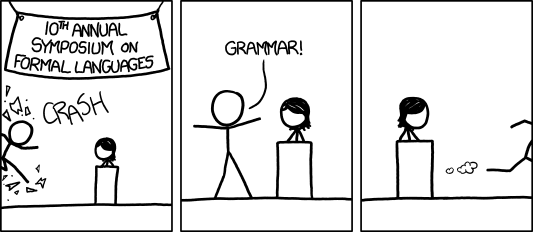

|

| XKCD is smarter than me. I can't speak for you. |

I think I'm a pretty smart guy, an opinion which on more than one occasion has got me exactly what I had coming to me. This morning I read the above XKCD comic. So, being a fan of language and all that it entails (witness this blog) I Googled "formal languages." Hey, I like to be in on the joke! What I could glean from the rat king of a Wikipedia entry on Formal Languages was that formal languages are the structures of language stripped of meaning.

This boggled me. I boggled.

I get that there is a point to analyzing the formal structures of language in order to...wait, what, again? There seems to be, in my head, a complete block on this one. I try to think about it or read about it, and my brain slides around it like a blind spot. I'd love some explanation of which I could make sense. Meaning seems to me to be of absolute necessity in language. Without meaning, the structure becomes useless. Since any given, functioning structure would do the trick for the communication of meaning, the structure seems to me a formality. If you don't have anything meaningful to communicate, then no structure will suffice to create that meaning. This may be a chicken and egg thing, and I freely admit to possibly missing the point.

This may be why I was never able to get my head around programming languages, though I loved the concept of futuristic machines that did our bidding. I was always better at story problems than solving formulas, better at playing music than taking tests on rules for composition, better at writing than memorizing rules of grammar and spelling. I'm sure I'm not unique in this. It may be simple laziness, a brain unused to a certain type of abstract thought unwilling to stretch at this late date.

Regardless, anybody who knows anything about this type of thing, anyone with a more scientific, abstract turn of mind, I'd love to hear from you. What do we do with Formal Languages? What are they for? What do they help us discover? And why, please God, why, is the above comic funny?

UPDATE: I think I get formal languages. The use of language when communicating with a computer obviates the expectation of meaning. In other words, when you're talking with people, you can speak about meaning. When you are sending commands to a computer that are undeniable, no meaning is needed or expected. The only pertinent question is whether the language is able to be parsed. Then structure becomes paramount. "Meaningful" means "able to be executed" and only language structured correctly becomes "meaningful." Structure becomes meaning.

Which still doesn't tell me why the comic is funny.

UPDATE: I think I get formal languages. The use of language when communicating with a computer obviates the expectation of meaning. In other words, when you're talking with people, you can speak about meaning. When you are sending commands to a computer that are undeniable, no meaning is needed or expected. The only pertinent question is whether the language is able to be parsed. Then structure becomes paramount. "Meaningful" means "able to be executed" and only language structured correctly becomes "meaningful." Structure becomes meaning.

Which still doesn't tell me why the comic is funny.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)